Author:Xiao Zinuo,The History Club of Beijing No.2 Middle School (Main Campus)

Abstract: The peasant wars at the end of the Ming Dynasty refer to the nationwide peasant movements that lasted for 37 years, starting from the 7th year of the Tianqi reign (1627) with the peasant uprising in Chengcheng County, Shaanxi, until the defeat of the anti-Qing base in Kui Dong in the third year of the Kangxi reign (1664). This is one of the largest and most intense peasant uprisings in Chinese history. The peasants, as the main force of the uprising, exhibited various demands for land policy reforms in different regions. These included Li Zicheng’s “land equalization and tax exemption” policy, the struggles over “equal tenancy” and “permanent tenancy” in the southeast, and the establishment of military farms by Sun Kewang, all of which had a significant impact on Qing and modern land policies. This paper, based on a reading of The History of the Peasant Wars at the End of the Ming Dynasty and related papers, analyzes the impact of geography, production methods, and politics on the land policies of the rebellious peasants, using examples from northern and southeastern China.

I. Attempts at Land Equalization in the North and Sichuan

Land Concentration and Social Crisis in the Late Ming Dynasty

At the end of the Wanli reign, over 230 years after the establishment of the Ming Dynasty, the government was plagued by internal corruption, intensifying land concentration, and a weakening of its power base. Among these contradictions, the land issue was the most acute. Due to a long period of domestic peace, the introduction of high-yield American crops, and a two-crop system, the population grew significantly to around 200 million, exacerbating the conflict between people and land. The corrupt bureaucratic system, the unchecked expansion of the landlord class, and the instability of smallholder farming further intensified land concentration.In this harsh environment, exacerbated by natural disasters, the crisis of the Ming Dynasty manifested itself in widespread rebellion and armed resistance, particularly in the northern regions. The highly centralized system of the Ming Dynasty and the power of local landlords and gentry contributed to the unprecedented brutality of the peasant wars and class struggles. The peasants’ demands for land redistribution and the punishment of the old aristocracy were significant. This was one of the primary reasons for Li Zicheng’s violent land equalization efforts after establishing his regime.

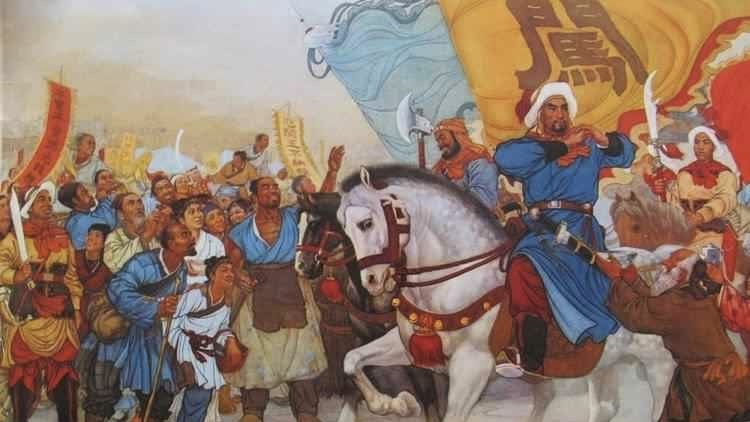

Li Zicheng’s “Land Equalization and Tax Exemption” Policy

In the 13th year of the Chongzhen reign (1640), Li Zicheng’s army broke out of the Shandong mountains and moved directly into Henan. After engaging in several large-scale battles with the Ming forces in cities like Luoyang and Kaifeng, Li Zicheng achieved a decisive victory. Upon capturing Luoyang, Li Zicheng began experimenting with land redistribution and wealth division, stating, “Noblemen and rich people oppress the poor, and when they see them starving and freezing, I kill them, so that they may experience the suffering of the common people.” This policy was immediately effective: “Hungry people from all around flocked to his banner, like a flood, day and night without end. When he called, a million would come, and his influence spread like wildfire.”Subsequently, Li Zicheng and his army adopted the slogan “Exterminate the soldiers, pacify the people” and “Land equalization and tax exemption.” After defeating the Ming forces under Sun Chuanting, they captured large areas in Henan, Shaanxi, Shanxi, and Hebei and established the Daxun regime in Xi’an. They continued their policy of exemption from taxation for three years and no killing of civilians. In their military campaigns, land was equally redistributed through force, and both rich and poor received land. The land redistribution was met with widespread support from the peasantry.

The Impact of Li Zicheng’s Land Equalization Policy

It’s important to note that land equalization was not a central policy in the Daxun regime. This was due to the severe exploitation under the late Ming ruling class, which led to mass migration and widespread land abandonment. As a result, large amounts of “ownerless” land became available, making land distribution easier. Furthermore, Li Zicheng targeted the land of the former nobility and gentry, many of whom had fled or been killed. The peasants, particularly those who had previously worked as tenants, could claim these lands with little resistance.

Geographical Factors in Land Equalization

The land redistribution process was easier in areas like the North China Plain and Guanzhong, where the terrain was flat and administrative costs were low. However, regions such as Northern Shaanxi and Gansu, characterized by hilly terrain and military garrisons, faced more difficulties in implementing land equalization.

II. The Struggle for Permanent Tenancy Rights in the Southeast

Special Conditions in the Southeast

By the late Ming period, the economic focus had shifted southward, with the southeast becoming the foundation of the Ming economy. The expansion of overseas trade and the inflow of silver led to the rapid development of capitalist agriculture in the region. As the economy grew, large landowners bought up vast amounts of land, leading to intense land concentration and a specific tenancy system. This system, marked by extreme exploitation of tenants, led to widespread discontent and peasant uprisings.

Armed Struggles of Tenants and the Fight for Permanent Tenancy Rights

The struggle for permanent tenancy rights was most evident in the “tenant soldier” and “Chopping Wang” movements in the southeastern region. In Fujian, leaders like Huang Tong organized peasants into armed groups to resist high rents and fight for permanent tenancy. They also sought to mediate land disputes and assert their rights to land that had long been dominated by wealthy landowners.

The Influence of Geographical and Economic Factors

The southeast’s geographical conditions, including its hillier terrain and the dominance of cash crops like tobacco, cotton, and mulberry, made it difficult for peasants to maintain a subsistence farming model. The move towards a more commercial agricultural system made tenants increasingly dependent on landowners, leading to the demand for more secure and permanent land tenure.

III. Conclusion

The land reforms during the peasant wars at the end of the Ming Dynasty were shaped by diverse political, economic, and geographical factors. Despite these differences, all the peasant uprisings shared a common revolutionary goal: to confront the concentrated land ownership of the Ming Dynasty and alleviate the burdens on peasants. These land policies, such as permanent tenancy rights, were later recognized as legitimate in Qing law, and attempts at land equalization served as a model for later revolutionary movements, such as Sun Yat-sen’s advocacy for land reform.

(This passage was edited by UHHC Operations Office)