Author: Larry Lu, Independent Member of UHHC

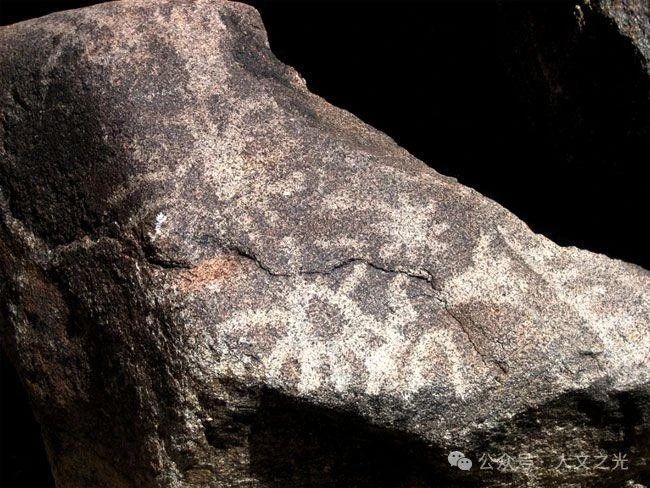

Imagine yourself as an ordinary laborer toiling under the sky on the second day of the fourth lunar month, Jingde 3 (May 1, 1006 CE). Suddenly, a star erupts in blinding brilliance—what would you think?

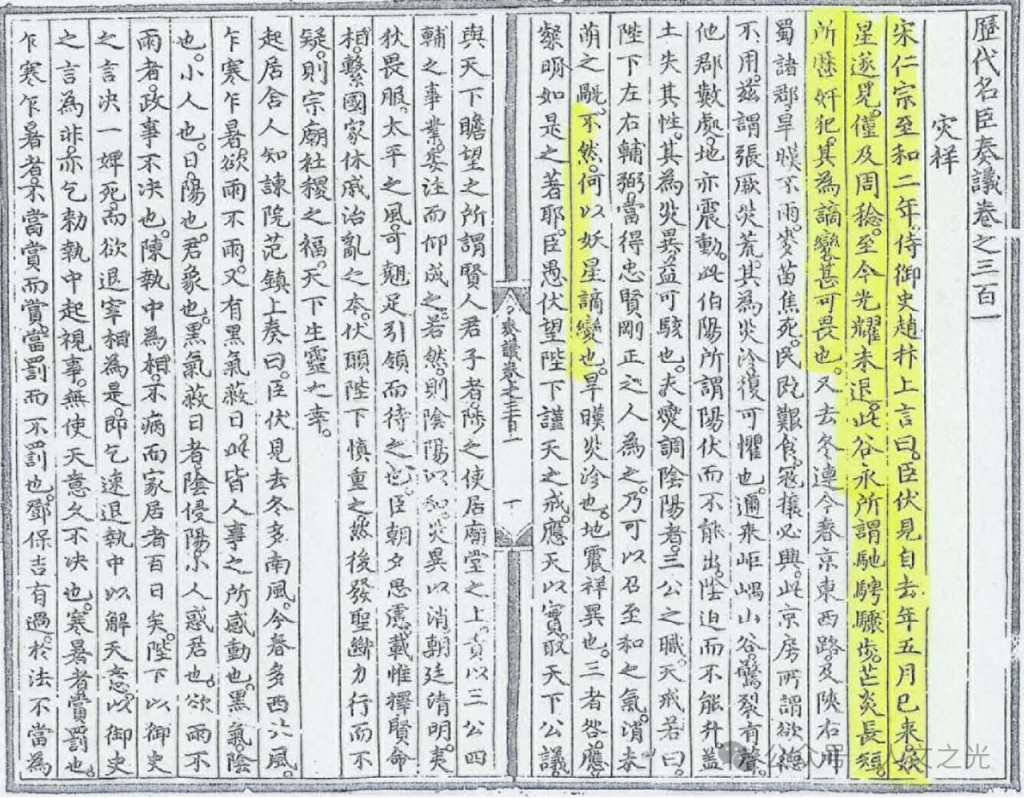

According to Song Shi (History of Song), Volumes 56 and 461, a star appeared west of the Di constellation (near Lupus, approximately 1° east of Centaurus) on May 1, 1006. At its peak, it outshone the crescent moon and cast shadows at night. By December, it reappeared in Di. Contemporary observers could not identify it—some called it the “inauspicious star of the nation’s sovereign” (国皇妖星), a “portent of war” (兵凶之兆). Astrologer Zhou Keming, returning to Kaifeng from Lingnan, reported to Emperor Zhenzong on May 30 that this golden, dazzling star was an auspicious sign heralding national prosperity.

Global records corroborate this phenomenon. Egyptian astronomer Ali ibn Ridwan noted in his commentary on Ptolemy’s Tetrabiblos:

“A spectacular circular body, 2.5–3 times larger than Venus… Its light illuminated the sky, outshining the crescent moon.”

Like others, he observed it low on the southern horizon. Monks at St. Gallen Abbey in Switzerland independently documented its position and brilliance:

“In wondrous fashion, it sometimes gathered, scattered, or vanished… For three months it lingered unchanged at the southern edge, surpassing all constellations.”

What was this phenomenon? A supernova—specifically SN 1006, the brightest stellar event in recorded history. Supernovae occur when nuclear fusion in a star ceases. Without outward thermal pressure to counter gravity, the star collapses. For massive stars, this triggers a cataclysmic explosion:

- Luminosity surges to billions of times the Sun’s brightness—rivaling entire galaxies.

- Shockwaves blast heavy elements (iron, carbon, oxygen, phosphorus) into space.

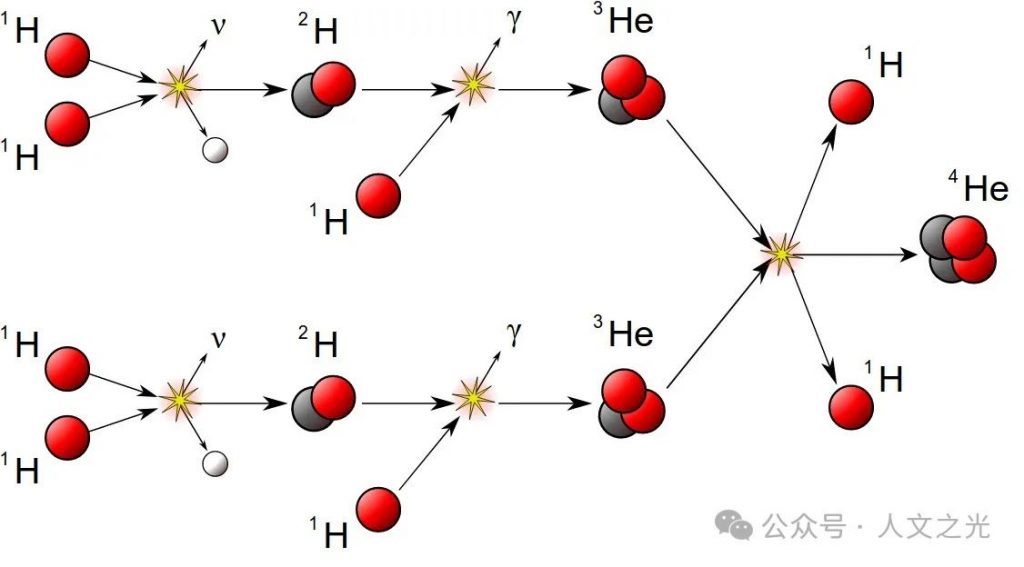

Nuclear fusion converts light nuclei (e.g., hydrogen) into heavier ones (e.g., helium), releasing energy. Reactions cease at iron/nickel—the peak of nuclear binding energy (optimal balance between strong force and Coulomb repulsion). Any fusion beyond this peak absorbs energy. Thus, without supernovae dispersing heavy elements, the universe would contain only hydrogen and helium.

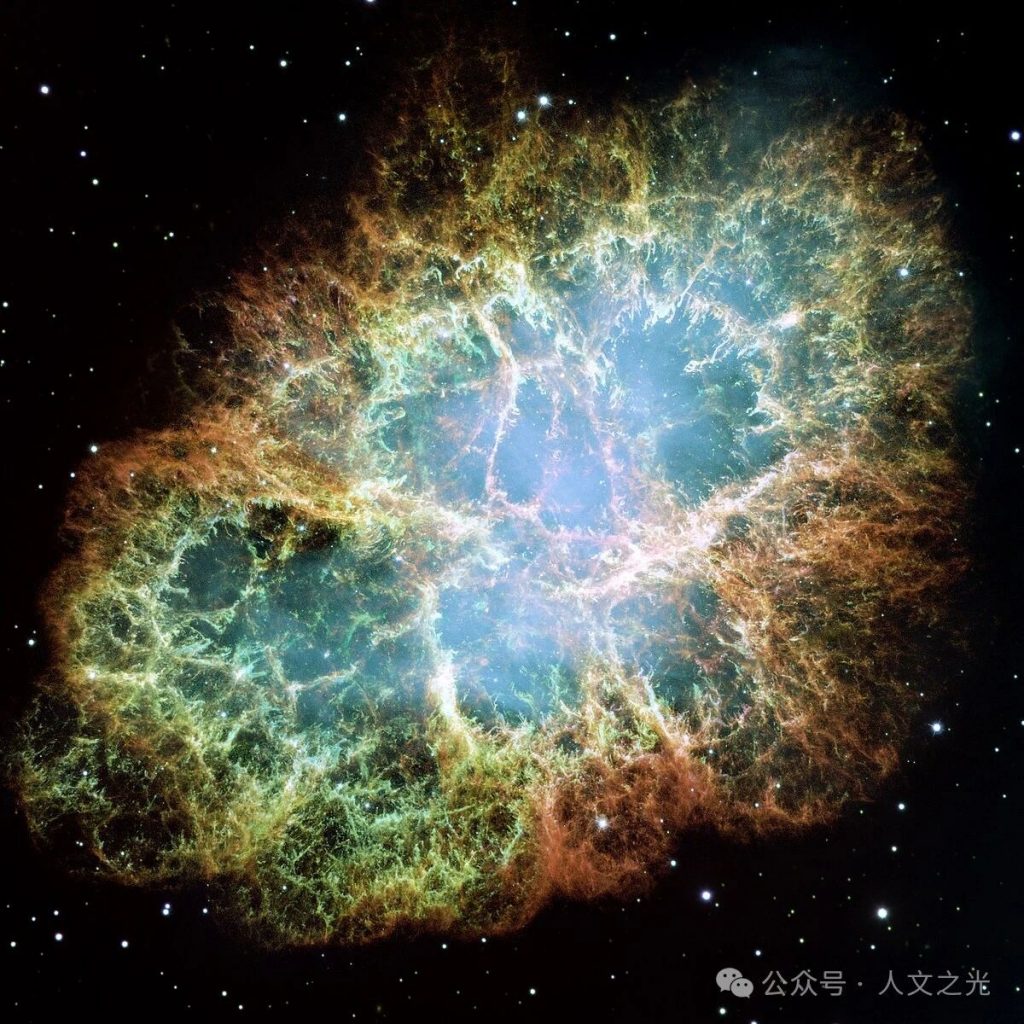

The supernova remnant—ejected matter colliding with interstellar gas—forms metal-rich clouds. These become raw material for new stars and planets:

- Earth’s iron core likely originated in ancient supernovae.

- Essential elements for life (C, O, P) spread via these explosions.

Meanwhile, the core evolves based on mass: complete destruction (white dwarf), neutron star, or black hole.

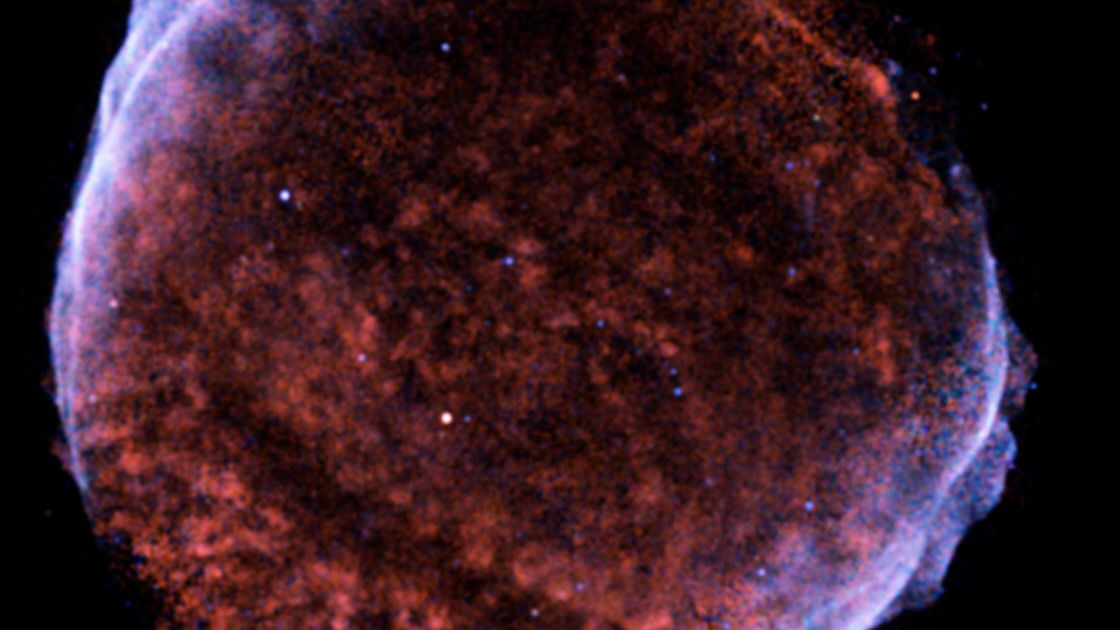

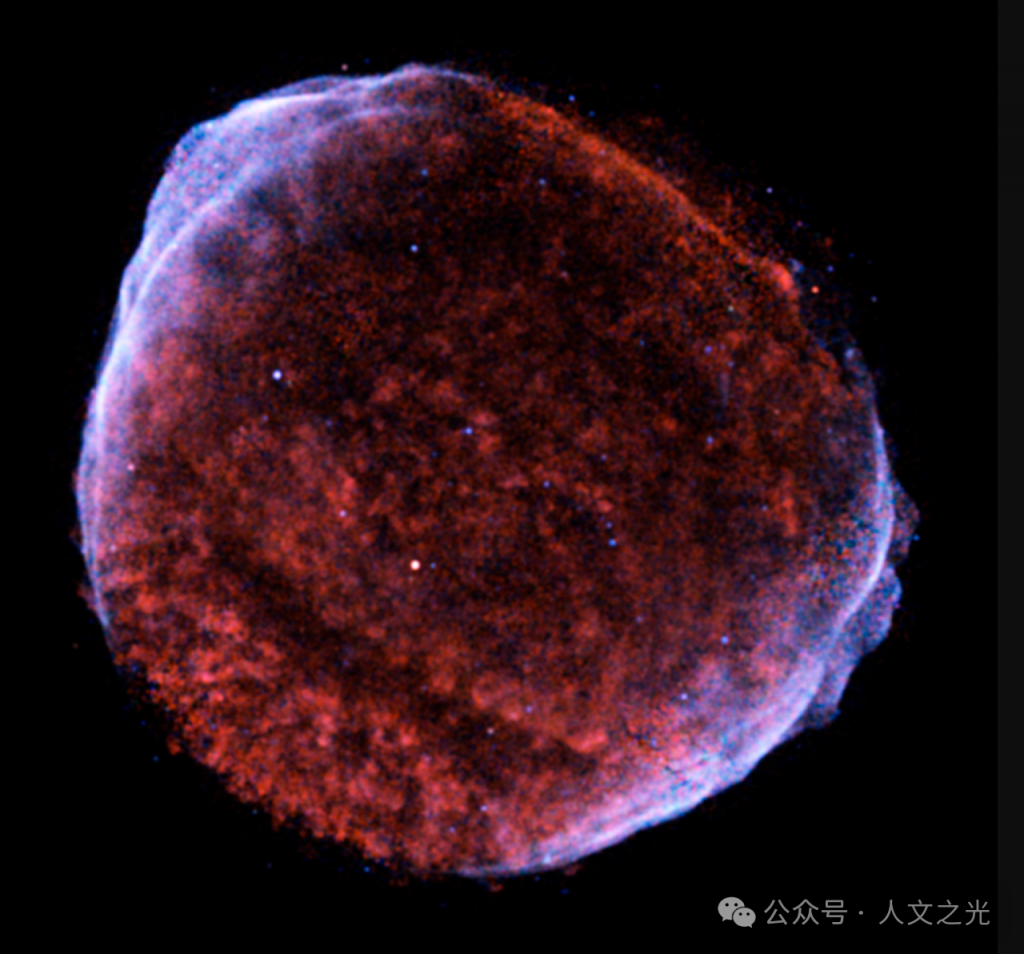

The universe’s most violent destruction is also its sacred crucible of creation. When we gaze at X-ray images of supernova remnants, we witness not just a star’s epitaph—but a cosmic epic of life written in stardust.

References:

- SN 1006, Baidu Baike https://baike.baidu.com/item/SN%201006/3721372

- Year 1006, Sogou Baike https://baike.sogou.com/v8647747.htm

- “How Powerful Are Supernova Explosions?” Zhihu https://www.zhihu.com/question/403950257

(This interdisciplinary article was edited by Peter Tian of the UHHC Operations Office. Images sourced from the internet will be removed immediately upon request if copyright is infringed.)