Author: D.Z from InkAndIron, Beijing SDSZ International Department

What military tactic immediately leaps to mind when you think about war? Assuredly the age-old method of encirclement, of isolating a part of the enemy within an enclosed ring, cutting off its retreat route and destroying it completely. All commanders strove for it. All students of the art learnt it in their textbooks. Yet, where did encirclement–or double envelopment–originate?

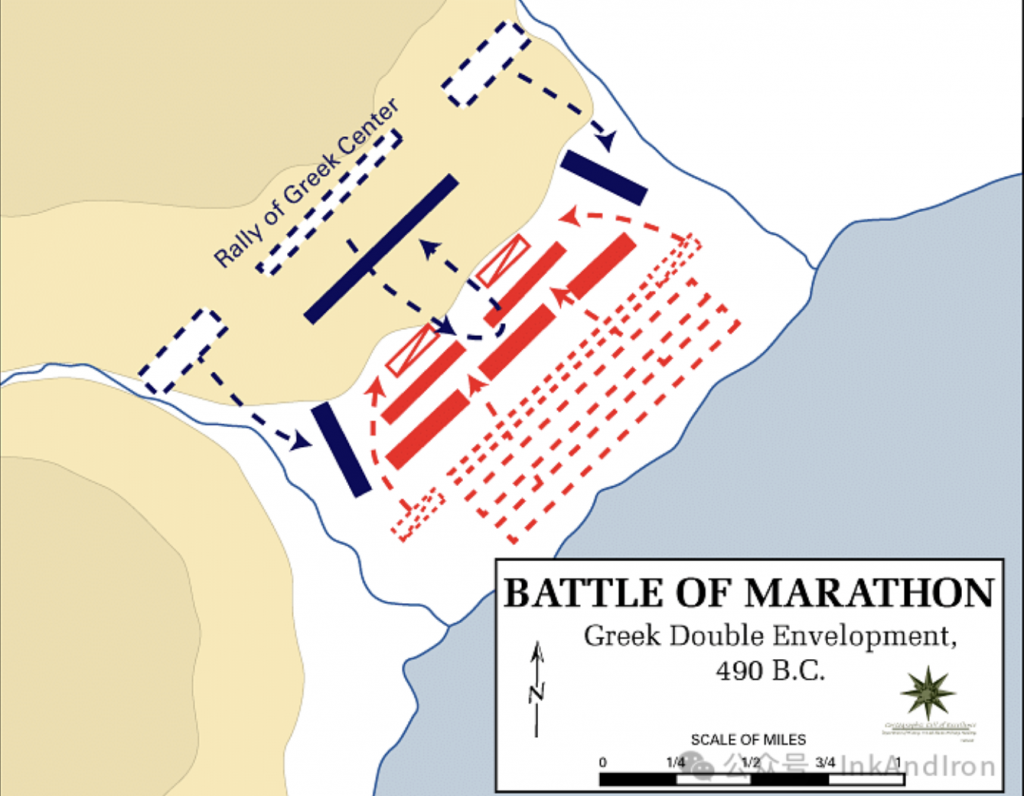

Perhaps you have heard of the Battle of Marathon, fought between the Ancient Greeks and the Persians in 490 B.C, after which Pheidippides is said to have run 40 kilometers from Marathon to Athens to deliver news of the crushing Greek victory. Miltiades, the Greek commander, had under him around just 10,000 men, facing around 25,000 Persian soldiers under Datis and Artaphernes. The trick here was the disposition of the Greek forces: Miltiades placed relatively few troops in the center–where the Persians were strongest and expected a frontal breakthrough, and instead placed his elite Greek hoplites, the heavy infantry, on their wings, facing the relatively weak Persian flanks. When battle commenced, the thin Greek center bended backward, yet the hoplites quickly defeated the Persian flanks and wheeled inward, surrounding the Persian center on both sides. The Persian center was crushed, and the survivors fled in rout back to their ships. Miltiades is said to have inflicted 5,000 to 6,000 casualties on the Persians, while just losing 203 of his own men.

If you will take a look at the map below, you can clearly see how the Persian center moved forward, how the Greek center fell back, and how the Greek hoplites moved inward from left and right, crushing the Persian center.

Looks simple and straightforward does it not? But it takes a cool head to come up with this plan when facing a numerically superior enemy.

Marathon was a decisive and ingenious victory. Yet it was not the “textbook battle” of antiquity. That honor belongs to Cannae alone. For in this great battle, fought on the Apulian plains of Italy between the Carthaginian forces of Hannibal Barca and the Roman legions under Gaius Terentius Varro and Lucius Aemelius Paullus, Hannibal managed to completely encircle an entire Roman army, and wipe it off the field. It nearly broke Rome.

The Second Punic War was a conflict between Rome and Carthage, two powers competing for dominance in the Mediterranean. Carthage had previously lost the First Punic War to Rome, and sought revenge, aiming to reclaim its former territories and status. War started in spring 218 B.C when Hannibal Barca, a Carthaginian general whose father Hamilcar had fought against Rome during the First Punic War, besieged and captured the city of Saguntum–a Roman ally–on the Iberian coast. In response, Rome promptly declared war.

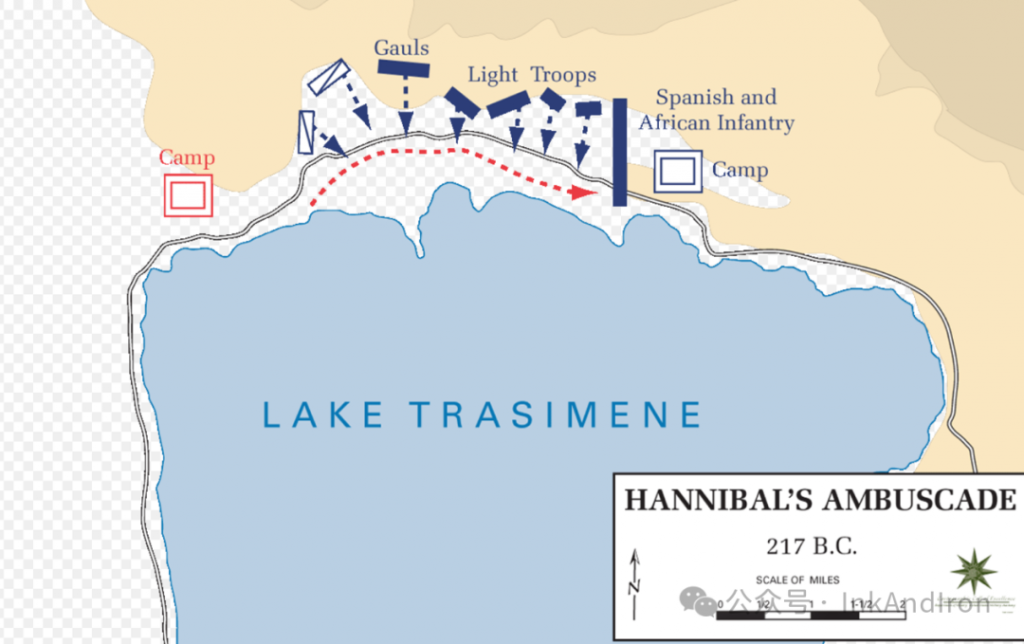

Hannibal then crossed into Italy by traversing the Pyrenees and then the Alps, emerging with a much reduced force of around 20,000 infantry and 6,000 cavalry due to brutal Alpine conditions and hostile tribes. In spite of this, he quickly gathered allies–local Gallic tribes hostile to Rome– and won major victories over the Romans at Trebia, where he executed an envelopment and inflicted 20,000 casualties on a Roman army of 40,000, and at Lake Trasimene, where he ambushed a Roman force, driving it into a lake and annihilating all 25,000 men along with a cavalry detachment of 4,000–effectively destroying two Roman armies.

These losses initially prompted the Romans to avoid pitched battles with Hannibal and instead try to cut his supply lines and wear him down. This strategy, known as the Fabian strategy–after consul Quintus Fabius Maximum who implemented it– soon became deeply unpopular with the Romans, who, after recovering from their initial shock, resolved to confront Hannibal directly with the largest army Rome had ever brought into existence at that time: 8 legions, totaling 86,400 men–80,000 infantry, 6,400 cavalry–facing Hannibal’s now 50,000-strong army, composed of 40,000 infantry and 10,000 cavalry. Yet Hannibal still held the advantage in cavalry, not only in quantity, but also in quality.

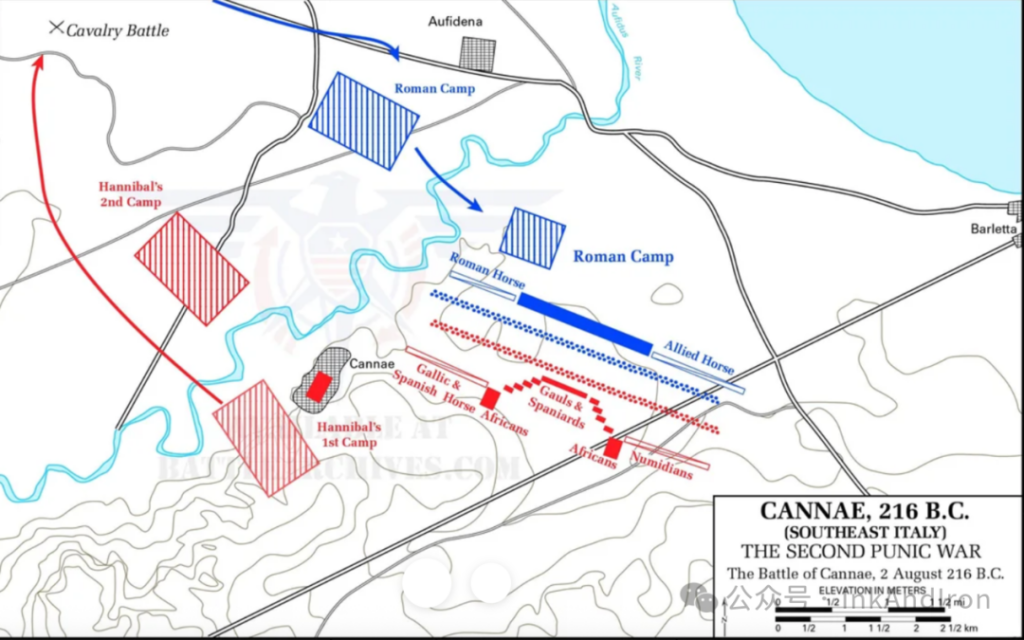

In spring 216 B.C, Hannibal, knowing that he faced a large Roman army, seized the Roman supply depot at Cannae and thus motivated the Romans to attack him at once. Both armies soon deployed on the flat stretch of ground between the Aufidus River and hills near Cannae. Here is a map of the deployment: the red blocks are the Carthaginians under Hannibal, and the blue blocks are the Romans under Varro and Paullus.

Notice something interesting? Hannibal placed his Gauls and Spaniards–lower-quality troops– in the center, forming the shape of a convex bulge that projected outwards. The goal of this odd deployment was to slow down the huge block of Roman infantry in the center to buy time for his superior cavalry to rout the Roman cavalry from the field. The Romans, after all, favored brute force to punch through the center. Also, he placed his elite African troops on the sidelines to the left and right (guess why).

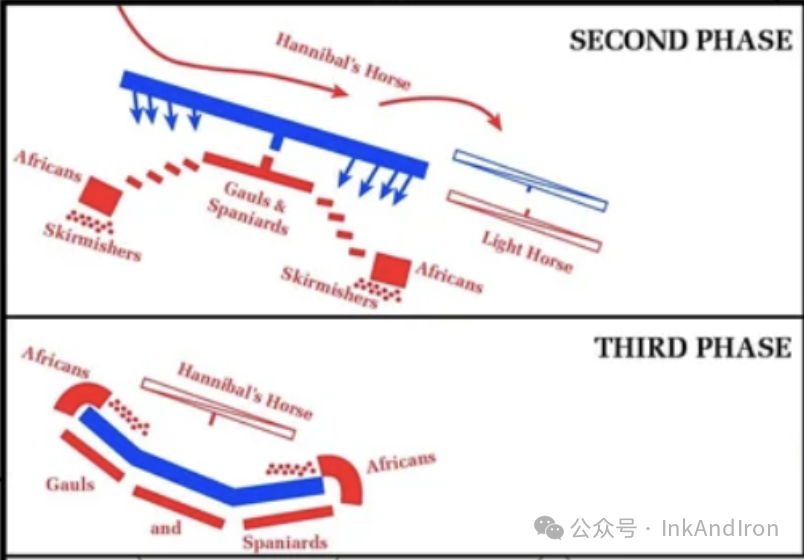

The battle began with the huge Roman center advancing as one against the thin line of Gauls and Spaniards in the center, gradually forcing it to give ground. At the same time, the Numidian cavalry on Hannibal’s right tied down the Roman allied cavalry, while Gallic and Spanish cavalry under Hasdrubal charged the weaker Roman cavalry on the left, soon completely routing it from the field. Instead of pursuit, Hasdrubal regrouped, and circled around from the back to attack the allied cavalry on the Roman right, which promptly fled the field, attacked from two sides. In the center, the massive Roman columns still ground forward, when suddenly the elite African infantry on the sides suddenly appeared on the Roman center’s left and right, now bereft of any cavalry, as shown in the maps below.

With the Gauls and Spaniards in the center, Africans to their left and right, and the Carthaginian cavalry now behind, the ring had completely closed around the Romans: they were now caught, with no hope of escape, even though they still technically outnumbered their enemy. The Romans soldiers still stood and fight desperately, but were gradually cut down by from all sides. It is hard to imagine the plight of the Romans, hemmed in into an ever-small space, unable to deploy or fight effectively, squeezed against each other, the air filled with the clash of weapons and smell of blood. The battle soon degenerated into a slaughter. As the historian Polybius wrote:

“as their outer ranks were continually cut down, and the survivors forced to pull back and huddle together, they were finally all killed where they stood.”

The historian Livy also described the scene:

“So many thousands of Romans were dying… Some, whom their wounds, pinched by the morning cold, had roused, as they were rising up, covered with blood, from the midst of the heaps of slain, were overpowered by the enemy. Some were found with their heads plunged into the earth, which they had excavated; having thus, as it appeared, made pits for themselves, and having suffocated themselves.”

Polybius and Livy differ on the total number of Roman casualties, but it seems certain that of the 76,400 Roman soldiers who fought on the field, at least 67,500 were lost at Cannae, killed or captured. Carthaginian losses did not exceed 8,000. This was a staggering blow. Hannibal had once again outwitted the Romans, and destroyed another Roman army with an inferior force. Rome descended into panic and chaos when they heard the news. By now, a fifth of Rome’s entire male population over 17 had been lost.

After Cannae, Hannibal tried to induce the Romans to open peace negotiations, yet the Romans would not compromise, and continued the war, though they never again tried to engage Hannibal in major combat on the Italian Peninsula, preferring to wear him down gradually under the Fabian strategy, and target the cities under his protection as by that time, nearly all of Southern Italy had defected to Carthage after Cannae. This would eventually cage Hannibal, as he relied on victories and could not defeat the Romans if they would not fight. In the end, the Romans forced Hannibal to retire to the southern tip of Italy due to manpower shortages, and launched their own invasion of Carthage. Hannibal was recalled to face this new threat, and met Publius Cornelius Scipio–who had rallied Roman survivors after Cannae–at the Battle of Zama, where he was defeated for good because for once, the Roman cavalry was superior. After this defeat on its own soil, Carthage sued for peace, ending the Second Punic War with Rome once more the victor.

Rome would eventually instigate a Third Punic War, after which they razed the city of Carthage to the ground and enslaved or killed its whole population in one of the most total acts of annihilation in ancient history. Hannibal, whom the Romans never truly forgave, was pursued relentlessly and eventually betrayed to the Romans. But instead of being captured, the general chose to take poison and ended his life, allegedly saying: “Let us relieve the Romans from the anxiety they have so long experienced, since they think it tries their patience too much to wait for an old man’s death.” After completely destroying the only other major power in the Mediterranean and truly coming of age through iron and blood, Rome would go on to forge a vast empire that would last for centuries. The Roman Republic would not suffer a defeat of such magnitude until the less-well known Battle of Arausio, when a Roman force of 80,000 troops and 40,000 camp followers was wiped out entirely by northern barbarian tribes. In terms of bloodshed and sheer tactical brilliance however, Cannae was the ultimate ceiling for Roman military defeat, the standard to which all later defeats were compared.Even the disastrous defeats at Carrhae, where Crassus was killed by the Parthians; Teutoburg Forest, where three Roman legions were annihilated by Germanic tribes; and Adrianople, which shattered the Eastern Roman army, led to the death of Emperor Valens, and hastened the Western Empire’s decline—none matched the sheer scale of Cannae, at least in terms of tactical execution, if not strategic consequence.

Cannae would go down in history as the “perfect battle”, and Hannibal’s use of the double envelopment there is cited as the first successful use of this tactic in the West to be recorded in detail, as well as one of the greatest battlefield maneuvers in history, influencing commanders to the present day. Many would try to recreate that total annihilation achieved at Cannae, yet few would ever replicate it fully. The Germans incorporated it into their military doctrine and used it at the operational level at Tannenberg in 1914 and multiple times on the Eastern Front in WW2, though the Schlieffen Plan, planned with Cannae as a basis for so long, was a failure. A battle like Cannae may well remain a romantic ideal of antiquity. Mayhaps Rome’s ultimate victory over Carthage serves as an indication that the young and new will eventually replace the old and crumbling. Yet even the mighty Roman Empire itself fell eventually. Nothing withstands the passage of time.

Well, here we are at the end. I sincerely hope this long passage has been enjoyable. For the next work, expect either another battle of brilliance from the West, or one from Chinese history.