Author: Ava Tian, Independent Member of UHHC from Shenzhen

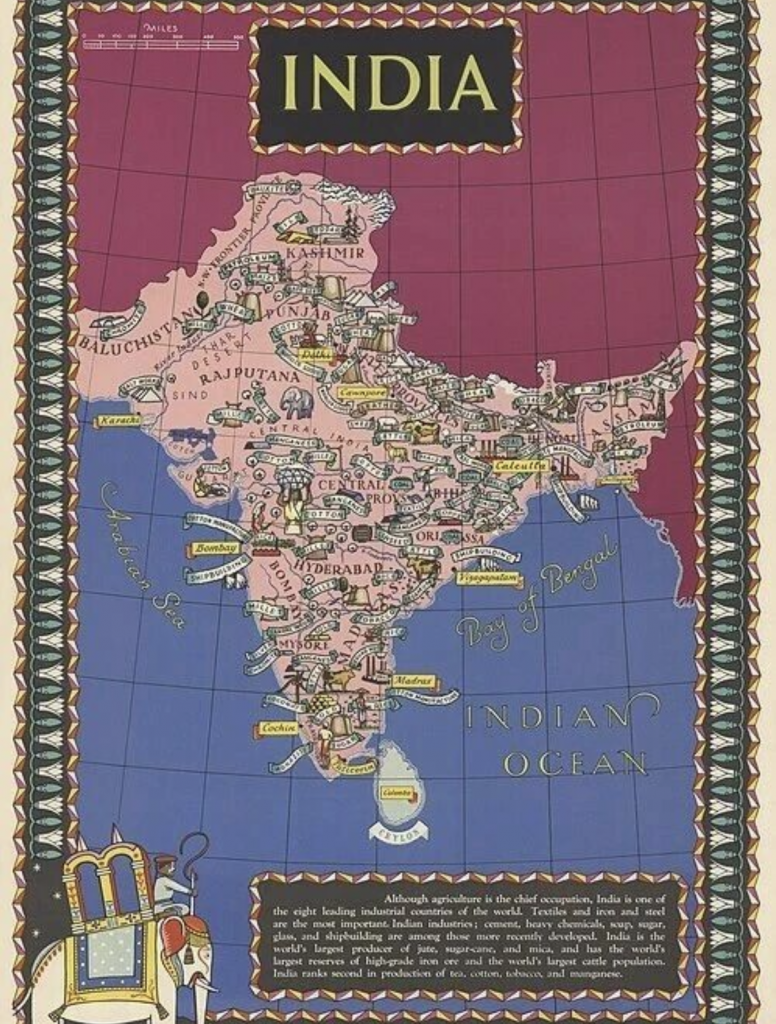

Modern day India was once the heartland of the world’s greatest land based empires. From the Maurya Empire to the Mughal Empire, India’s legacy continued until the arrival of a group of ships owned by a newly emerged maritime empire–Britain. Backed by steamships and industrial might, Britain slowly expanded across continents covering around a quarter of Earth’s land surface and ruling over 458 million people (Kane, 2020). One of its major colonies was India that started with the establishment of the first trading post of the British East India Company (BEIC) in 1612. The BEIC gradually expanded its influence in India until it controlled India as a whole. After the 1857 rebellion that forced administrative changes, direct British colonization of India began in 1858 when the rule of the East India Company was transferred to the Crown in the person of Queen Victoria.

To what degree did Britain tolerate local cultural practices into their empire? To what extent was this toleration, or lack of toleration, justified and why? This paper argues that while allowing certain Indian religious customs to minimize resistance, British toleration of Indian cultural practices was selective, limited and instrumental, primarily serving colonial control rather than genuine respect for local traditions through changes in the legal order as well as western reforms in education.

The British colonial administrative government permitted specific Hindu and Muslim customs in order to mitigate local resistance against colonial rule. In British established local courts regulated by the British Crown, British judges relied on maulavis and pandits to advise matters of personal law, indicating respect for traditional Indian authority (Huda, 2003). The usage of indigenous advisors–maulavis for Muslim law and pandits for Hindu law–to guide the British judicial system on personal law matters related to local traditions. This demonstrates British recognition of existing religious legal traditions rather than forcibly enforcing an entirely foreign legal system, signaling a deliberate choice to respect traditional native legal frameworks influenced by religion. Thus, the role of local advisors in British courts exemplifies the attempt of the colonial government to maintain religious diversity while introducing a new judicial system. William Jones, a British philologist, argues in his writings the significance of Indian scholarship, particularly Sanskrit literature, for understanding human history and supporting biblical accounts (Alun, 1996). The claim made by a famous British scholar implies the willingness to engage seriously with local Indian literary traditions rather than dismissing them outright with English literature. Jone’s action reveals deep respect for Indian cultural aspects. By interpreting local works in an unbiased way, Jones firmly asserts his respectful stance toward local cultural practices within the imperial framework. Jones likely constructed his argument in order to show hostility toward Eurocentric attitudes criticizing western judgements of Eastern literature based on imperialistic ideas such as Social Darwinism.

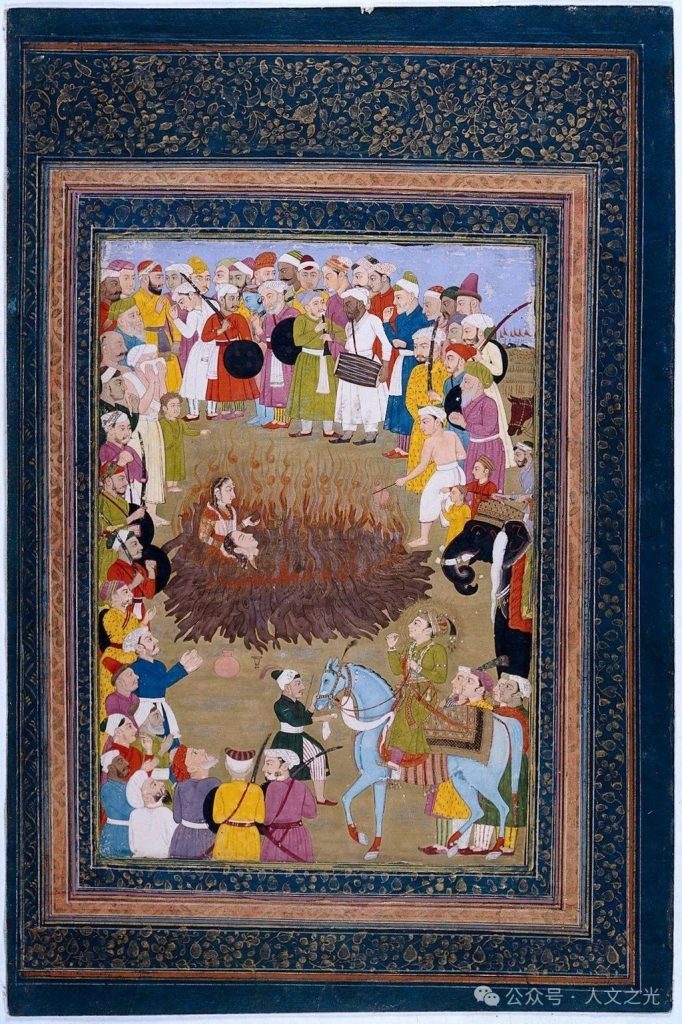

While the British co-opted religious legal systems, their social reforms destructured local traditions. Ram Mohan Roy, under the influence of British values, led a social reform movement that abolished the practice of a local tradition—Sati (Parbury, 1832). Despite the good intention of banning Sati as a rejection of immoral practices, it reflects a British view that local Indian traditions are considered as barbaric and must be stopped. To add on, British actions to actively address and ban Sati does not imply care for local Indians but rather viewing Indian traditions as regressive. This promotes a sense of urgency for a need of social reforms designed for convenience of imperial rule under British values rather than considering local cultures. In which British intolerance of local traditions is constructed through moral condemnation in order to delegitimize cultural practices such as Sati by framing it as oppressive to justify its prohibition under British rule. Furthermore, Britain’s efforts to reform society excluded ethnic minorities as they were not recognized as full citizens but rather designated as “trainee Brits” (Pathak, 2005). This framing set by the colonial government excluded minority groups from owning citizenship as well as limited participation to national aspirations. These actions emphasize how British governance led reforms that encourage inclusivity marginalizing the minorities that exist in the nation. To add on, multicultural policies that are conducted were a part of a greater strategy that did not challenge structural racism or state power but rather a method to manage cultural differences and attempt to maintain stability in the status quo. Despite the fact that these policies were meant to promote multiculturalism it’s only purpose is to manage differences but not embracing the differences. Therefore, suggesting such societal reforms were based on the premise of social control and strengthening governance rather than about encouraging true equality and respect for local cultural practices.

In addition, education reforms conducted by the British government lack consideration of local customs and focus solely on British values. Former Paymaster General of the UK, Thomas Macaulay explicitly claimed traditional Hindu and Muslim learning as “false history, false astronomy, false medicine” and mocked native geography as involving “seas of butter” (Elmer, 1953). Macaulay’s views showcase a dismissive attitude toward native customs and pressures assimilation within the native population leading to loss of cultural identity. Macaulay’s beliefs ultimately led to Macaulay’s Minute on Education in 1835 that sought to create a class of Indians who would be educated in the English language and Western knowledge. This education reform advocated by Macaulay was primarily based on teachings of Christianity indicating a goal to “civilize” Indians as these Evangelical leaders believed that English education was necessary to eradicate social “evils” offered by traditional Indian religion. The complete rejection of local traditions evolved around claims that Sanskrit and Arabic studies were useless that largely ignored existing culture. On the other hand, Indigenous gurukul and madarsa systems were not banned outright but instead systematically marginalized in favor of English education after Macaulay’s Minute on Education, due to the prioritization of first hand British education of elites and reformers who treated local teachings as “useless”. Thus, with British reformers introducing changes to the Indian education system, local culture was slowly diminished in the process causing cultural assimilation in the population, especially the younger generation as they were the primary targets of the new educational system.

To sum up, India was under British colonial rule for almost 200 years despite the infrastructure and knowledge that was built and introduced. Something greater was lost through these years of direct colonial rule such as oral traditions and regional language due to limitations of local culture imposed by the colonial administration. Major cultural beliefs were still passed down due to the numbers of Hindus and Muslims in the community, but smaller things like cultural identity were blurred under gigantic waves of westernization with Christian values and morals. Although Britain allowed groups to maintain their religion, tolerance to local cultural practices were relatively low as shown in social and educational reforms built for the purpose to consolidate rule rather than authentic care and respect. Although independence was achieved after the partition of India in 1947, British sentiments still remained in postcolonial India, influencing its society and education of new generations.

(Edited by Peter Tian from UHHC, The pictures are from the Internet. If it infringes any rights, we will delete it immediately. All the copyrights of this article belong to the author Ava Tian. Anyone who infringes will be held accountable by both the author and UHHC to the fullest extent.)