Author: Hua Tu, Zeitgeist: An Open Quarterly for Ethics and Human Values, a UHHC partner organization

Chinese art is a tapestry woven by skilled painters, learned literati, and diligent craftsmen, reflecting the nation’s boundless creativity and life-affirming spirit. Each historical era birthed unique artistic expressions, shaped by political landscapes and cultural shifts.

Pre-Qin Period: The Bronze Age of Art

During the Pre-Qin era, as slavery thrived, bronzeware emerged as the primary artistic medium. Vessels adorned with animal motifs and intricate patterns embodied the creative vigor of the time. These bronzes weren’t just functional—they were spiritual artifacts, blending practicality with symbolic meaning.

Qin and Han Dynasties: The First Golden Age

After Qin Shi Huang unified China, and under subsequent Han rulers, art flourished. Tomb excavations reveal Qin-Han customs through lacquerware and coffins. Dominant cloud patterns suggested a belief in posthumous happiness, while stone reliefs depicted noble life—horses, battle scenes, and kitchens—with striking realism. This period marked the rise of decorative art as a narrative tool, capturing both daily life and spiritual aspirations.

Wei, Jin, and Northern-Southern Dynasties: Buddhism’s Artistic Impact

With Buddhism’s spread, grotto art surged. The Mogao Grottoes in Dunhuang became a beacon of Sino-Western cultural exchange, housing flying Apsaras, philosophical story paintings, and sutra illustrations. These caves weren’t just religious sites—they were galleries of cross-cultural innovation.

Tang Dynasty: A Pinnacle of Grandeur

The Tang Dynasty represents an artistic zenith. Figure paintings, landscape scrolls, flower-and-bird motifs, cave murals, and colored sculptures thrived in a society defined by openness and optimism. Artists like Wu Daozi brought figures to life, while landscape painters captured nature’s majesty.

As one scholar lamented, “Even years of study can’t fully convey Tang art’s vibrancy—it embodied a civilization at its peak.”

Song Dynasty: Ink Landscapes and Literati Expression

Facing governance challenges, Song scholars turned to ink landscape painting as a political statement. Fan Kuan’s Travelers Among Mountains and Streams used bold brushwork to evoke nature’s grandeur, reflecting scholars’ yearning to reclaim northern territories.

Literati painting emerged, prioritizing emotional resonance over realism. Painters like Mi Fu pioneered “ink splashing” techniques, blending art with poetry and calligraphy.

Yuan, Ming, and Qing Dynasties: Synthesis and Continuity

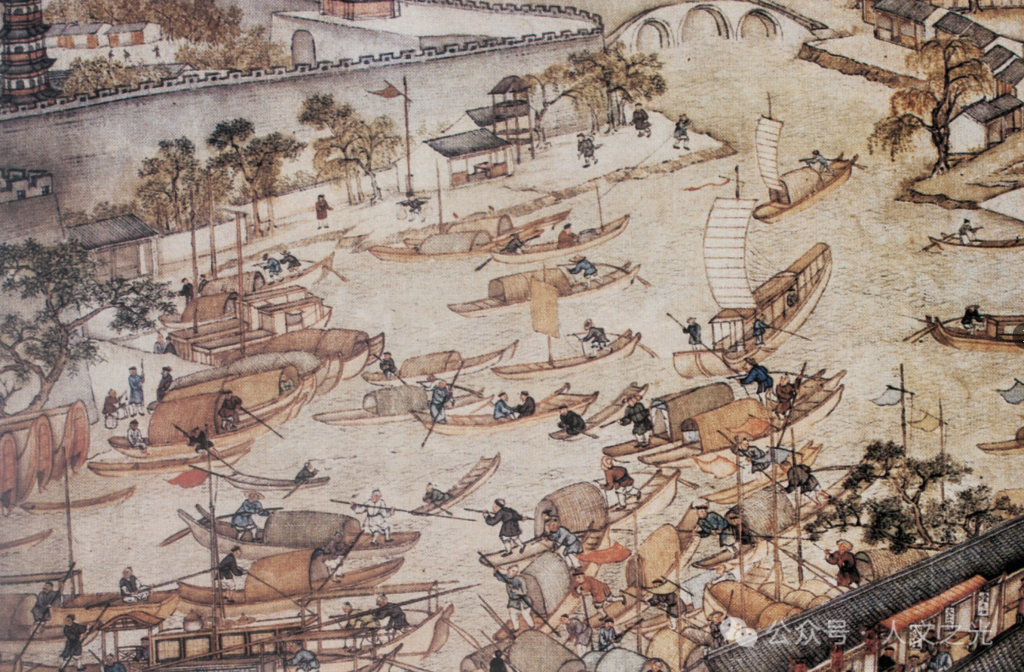

While Ming-Qing art showed potential for innovation, imperial policies favored stylistic synthesis. Huang Gongwang’s Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains and Xu Yang’s Prosperous Suzhou exemplify this era’s mastery.

Scholars compiled art theories, preserving ancient techniques. Yet creativity persisted—”Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou” rebelled with avant-garde styles, proving art’s enduring ability to adapt.

Epilogue: Art as a Living Legacy

For millennia, Chinese art has been a mirror to the soul—from bronze rituals to ink wash philosophy. In the modern era, its legacy endures not as a relic, but as a wellspring. As we revisit these masterpieces, we uncover not just history, but a timeless truth: art is how civilizations remember, heal, and dream.

From Dunhuang’s caves to contemporary installations, Chinese art reminds us that creativity, like the Yangtze River, flows ever onward—carrying the past into the future.

(This article is from Zeitgeist: An Open Quarterly for Ethics and Human Values, a UHHC partner organization. Edited by Peter Tian from UHHC, The picture is from the Internet. If it infringes any rights, we will delete it immediately. All the copyrights of this article belong to the author. Anyone who infringes will be held accountable by both the author and UHHC to the fullest extent.)