Author:Yusuf Wang, The Hi-Storyteller Humanities and History Club (2024-2025) from Beijing No.2 Middle School International Division

In May 1755 (the 20th year of the Qianlong Emperor of the Qing Dynasty), the Qing government sent troops to suppress the Amursana rebellion in Xinjiang, rescuing the Khoja brothers (Khoja Kalan and Khoja Kichik). However, these two later organized their own rebellion. The Xinjiang Khoja family was divided between the Apak Khoja and the Elemett Khohoja factions. Rong Fei (the legendary “Xiang Fei” or Fragrant Concubine) and her family belonged to the Elemett Khoja faction, which supported the Qing court and opposed separatism, suffering persecution from the Khoja brothers. In 1757, the Qing court again sent troops to Xinjiang to suppress the Khoja brothers’ rebellion. Rong Fei’s uncle and brother actively cooperated with the Qing army, and the rebellion was quelled by 1759. In 1760, Rong Fei’s elder brother, fifth uncle, sixth uncle, and five other leaders were summoned to Beijing, where they were awarded official titles and ranks by the Qing court, an event historically known as the “Entry of the Eight Nobles.”

The Qianlong Emperor incorporated this group, led by the eight Hui (Muslim) leaders and religious figures, into the Eight Banners, decreeing their settlement in the area south of the Xiyuan Baoyue Lou (today’s Xinhua Gate in Zhongnanhai), around present-day Dong’anfu Hutong. This settlement became known as “Huihui Ying” (Hui Camp), also called the “Red-Hatted Huihui.” Xiang Fei, who accompanied her uncles and brother to Beijing by imperial decree, entered the palace and was bestowed the title “Noble Lady He” by the Qianlong Emperor. Subsequently, the Emperor ordered the construction of the “Qingzhen Puning Si” (Mosque of Universal Peace) within the Hui Camp for its inhabitants to worship.

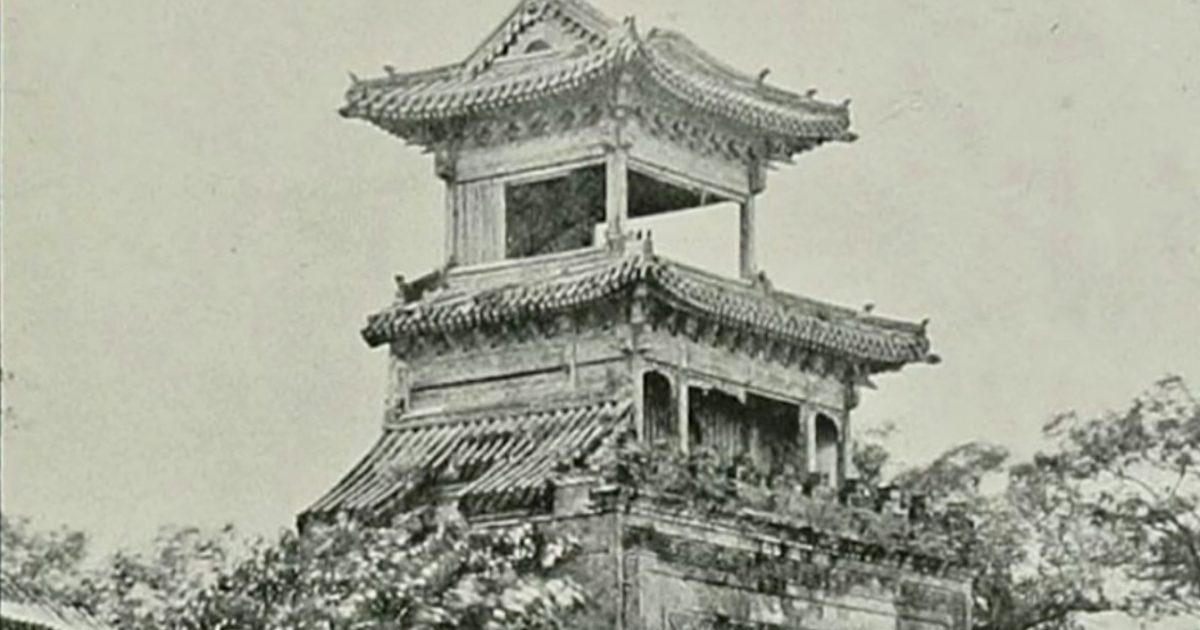

The Qingzhen Puning Si was founded in 1762 and completed in 1763, situated directly across the street from the Baoyue Lou in Xiyuan. This was an imperially authorized mosque, funded directly from the imperial treasury and constructed under specific supervision. Notably, it was the only mosque directly built by the Qing government. Muslims from the surrounding Hui community worshipped there at the time. The mosque’s architecture was unique: its main gate was strikingly ancient in style, built from massive stone blocks resembling a city gate, encircled by crenellations, creating an extremely solemn atmosphere. Above this was a small room with brilliant vermilion walls, like a temple. Further above was a room with windows. At the very top was another small chamber, open on all four sides without doors or windows. In total, it had four levels, standing over two zhang (approx. 6.6 meters) high. Passersby felt as if they had been transported to the Western Regions. When Xiang Fei resided peacefully in the palace and missed her home, she would ascend a tower and gaze southward to soothe her longing. Thus, it was popularly called the “Wangjia Lou” (Gaze-Home Tower). South of the administrative office was the prayer hall, built at the same time, with a stele recording its history.

The Qianlong Emperor personally composed and wrote the stele inscription for the Qingzhen Puning Si. This stele is the only known mosque stele text handwritten by an emperor. After liberation, it was buried underground for a time, later recovered by cultural relics authorities, and is now housed in the eastern section of the Beijing Ancient Observatory. The stele contains text in four languages: Manchu, Han Chinese, Mongolian, and Hui (likely Arabic/Persian script). The content is as follows:

As the sovereign lord of all under heaven, I cause those in distant lands to hear our commands and uniformly adhere to our regulations. Thereafter, wherever military law extends, no local customs dare assert selfish interests – this is the highest principle. Yet, considering antiquity, those charged with managing elephant stables and translating tongues necessarily communicated intentions and desires [between peoples], cultivating their teachings without altering what was suitable to them. How could our fundamental aim be contrary to theirs? It is precisely by reaching the utmost of the world’s diversity that we achieve its great unity, and those who observe our transforming influence increasingly see it as all-encompassing.

Examining historical records, the Uighurs first entered China during the Sui Dynasty’s Kaihuang era. By the early Yuanhe era of the Tang Dynasty, they came with Manichaeans to present tribute and requested to establish a temple in Taiyuan, named “Dayun Guangming” (Great Cloud Brightness). This indeed marks the origin of the mosque. However, the means by which they arrived – whether borrowing teachers to facilitate trade – did not truly align with the principle of submitting land and people to become our subjects and servants.

I, reverently receiving the great blessings of Heaven, Earth, and our Ancestors, pacified the Zunghars and thereby stabilized the various cities of the Muslim regions. Their Begs, Khojis, Khošiq, etc., were granted titles of princes and dukes, and were bestowed with official residences. As for the remainder of the people who were not permitted to return to their native lands, they were settled west of the Chang’an Gate, so that they might serve in offices and perform duties, receiving lodging. The capital’s inhabitants thus came to call it the “Huizi Camp” (Camp of the Muslim People). Now, where numbers multiply, supervision becomes complex; where kinds are distinguished, sentiments tend to diverge. Contriving how to unify the common and join the different, so that what is seen and heard lacks strange distortion, lies fundamentally not in suppressing their religion and forcibly bending it.

Furthermore, since the Four Oirat tribes of Zungharia submitted, we have successively constructed, for this purpose of gracious pacification, temples like the Puning Si and the Gù’ěrzhá Temple. The Muslim people are also our people; how could we allow them to feel wanting? Therefore, I commanded the responsible officials to draw upon surplus funds from the imperial treasury to build this mosque at a central location within their settlement. With its vaulted gateway, bright hall, protective arcades, and encompassing eaves, it fully meets the proper standards.

Construction began in an auspicious month of a harmonious spring in the Guiwei year [1763] of Qianlong and was completed within one year. The Muslim people gather beneath it seasonally, and the various Begs who come in rotation year after year for audience are all overjoyed to gaze upon it and pay reverence. They marvel, declaring it unseen even in the Western Regions, asking if any have enjoyed the recent honors [bestowed by us] while simultaneously possessing the beauty of their native customs in such a project as this? They reverently bow and say: “It is so.” I further solemnly instruct them: “Your Muslim customs formerly knew only the鲁斯讷墨 (Sharia/Law); now you follow the calendar and honor the court’s ceremonies. Formerly you knew only the Tenge (silver coin); now the Mint casts and issues currency. Extending to ordinances for garrison taxes, audience banquets, and other major institutions, none fail to harmonize with our sound teachings. And the state, applying the principle of governing men through men, further acts by following your religion to harmonize your community. Considering the myriad dances, the skills of the tightrope, the ranks of the nine guests with their headdresses – this project and this intention are precisely thus.” Who can say it is not proper?

The stele was dated the auspicious mid-summer month of the Jiashen year in the 29th year of Qianlong (1764), Imperially Composed and Written.

( For brevity in this summary, it’s noted that the text explains the Emperor’s role as universal sovereign, the history of Muslims in China, the pacification of Xinjiang, the settlement of the Hui community in Beijing, the rationale for building the mosque to unify and accommodate different peoples under Qing rule without suppressing their religion, descriptions of Islamic beliefs, and the construction details.)

It was once mistakenly rumored among the people that this mosque was the “Xiang Fei Temple,” and that the Baoyue Lou was built by the Qianlong Emperor for Xiang Fei. The legend claimed her parents, missing their daughter and unable to enter the palace, would ascend the mosque’s minaret (Bangke Lou) to gaze across the street at Xiang Fei in the Baoyue Lou, leading to the popular name “Wangjia Lou” for the tower. In reality, the mosque was never officially called the “Xiang Fei Temple,” but the Hui Camp and Baoyue Lou were indeed connected to Rong Fei. Many of her clansmen lived in the Hui Camp. Although the Baoyue Lou was built two years before Rong Fei entered the palace (1758), poems by the Qianlong Emperor about the tower suggest she likely visited or stayed there multiple times. Three years after Rong Fei’s death, the Emperor, still in front of the Baoyue Lou, wrote a poem: “For thirty years the portrait (likely of Rong Fei) was always similar, / New Year’s poems past and present are the same.”

Originally, a long wall stood south of the Baoyue Lou. In the early Republic of China, the section closest to the tower was demolished, revealing the entire structure, which was renamed Xinhua Gate (New China Gate). When Yuan Shikai was in power, he established the Presidential Palace here, and this gate became its main entrance. Directly facing this gate was the minaret of the Huiziying Mosque. After Yuan’s brief “Hongxian” imperial reign, he often worked late in his “Jurentang” office in the residence. Late at night, he would hear loud recitations from the south. Listening carefully, this non-singing, mournful, and solemn sound made his hair stand on end, sending chills down his spine. He later discovered it was the Imam of the Huiziying Mosque performing the dawn prayer (Fajr) call to prayer (Adhan). That Yuan, with his ghostly and furtive style of governance, was frightened by this, is no wonder his hold on power was as brief as a flower’s bloom.

At that time, the Imam of the Huiziying Mosque was Imam Ma. The Ma family were originally from Aksu, Xinjiang (present-day Wensu), Uyghur Muslims who had come to Beijing with Xiang Fei. They had lived there since the mosque’s founding, with generations serving as Imams. In the early Republic period, Yuan Shikai, misled by feng shui advisors who claimed the mosque’s direct alignment with the government was inauspicious, sent officials to Imam Ma Enrong to negotiate relocating the mosque. Imam Ma, considering the gravity of the situation, convened several meetings with the mosque’s trustees and fellow Northwesterners. They concluded that as this mosque was significant for the Uyghur Muslims in the city, with over 200 years of history, culture, religion, and unique relics, they could not agree to relocate and rebuild.

Unexpectedly, Yuan, failing to get the Muslims’ consent, became furious. Under the pretext of road widening, he sent hundreds of workers to completely demolish the mosque’s main gate, minaret, and main prayer hall. From then on, the Huiziying Mosque, associated with the Northwestern Uyghur Muslims, was never the same.

The mosque’s financial situation also declined drastically. During the Qing, the Bannermen lived on state stipends, so the mosque’s operations were supported by these Hui Bannermen of Uyghur descent. After the Republic’s establishment, these stipends became irregular and were completely canceled by 1915. When Yuan demolished the mosque, news within the Muslim community was not as widespread as today, so few knew about it. Furthermore, as the mosque was primarily used by Hui Bannermen, they lacked external support and faced many obstacles, leaving the once majestic and splendid Huiziying Mosque in ruins.

After the demolition, worshippers, having no place for prayer, temporarily used two side rooms in the eastern part of the mosque compound. Soon after, prominent community members like Yang Zhongxian initiated the construction of a few small rooms on the original foundation of the main hall to serve as a temporary, smaller prayer space. After Yuan’s demolition, a long wall was built along the northern part of the site near the road, blocking the original entrance. Consequently, the entrance was changed to face south, accessed from Wenchangge Hutong. Over the years, the mosque was barely maintained by the Ma family Imams. Observing that even the Friday prayers led by the Imam were sometimes held at other mosques indicates the decline of the religious foundation of the Hui Camp community.

After the northern main gate was demolished in 1913, the Qingzhen Puning Si opened a new southern gate on the middle section of the north side of Dong’anfu Hutong, facing south. After liberation until 1966, the mosque continued its activities normally. In 1966, it was converted into civilian housing. Before 2009, remnants still existed, including: the southern gate ruins, featuring an arched stone doorway carved with intertwining floral patterns; a main hall in the courtyard north of the gate; and the Qianlong Emperor’s stele north of the hall, directly opposite Xinhua Gate, which had been moved to the Ancient Observatory before 2009.

In 2009, during the West Chang’an Street road widening and demolition project, all buildings on the north side of Dong’anfu Hutong were razed. The architectural remains of the original Qingzhen Puning Si site thus vanished completely. The Xicheng District Cultural Committee reconstructed a small courtyard 200 meters west of the original site, but it has never been opened to the public.

Sources:

[1] “The Mysterious Woman Qianlong Could Not Forget: Revealing the True Identity of Xiang Fei.” People’s Daily Online. 2012-11-07.

[2] “Dong’anfu Hutong: A Mosque Related to Xiang Fei.” Phoenix Net. 2009-06-09.

[3] “Farewell to Old Chang’an Street.” NetEase. 2009-04-20.

[4] “The Story of Baoyue Lou, Huihui Ying, Xinhua Gate, and the Big Flower Wall.” Old Beijing Net. 2009-05-05.

Partial Image Source: “The Vicissitudes of the Huiziying Mosque – Starting from the internal photos taken by Teacher Meibing Zhaobing.” Old Beijing Net. 2008-10-22

(This article was edited by Peter Tian of the UHHC Operations Office. Images are from the internet; we will remove them immediately if copyright is infringed. Full copyright of this article belongs to the author Yusuf Wang; UHHC and the author will pursue responsibility for any infringement.)