Author: An Anonymous Independent Member of UHHC from Shenzhen

Disclaimer: This essay is based on the second question of the Economics track for the 2025 John Locke Essay Competition. It was written after the competition’s submission deadline and was NOT entered for judgment. Its sole purpose is to fulfill an assignment for the author’s economics class.

Introduction

From January 2025 on, the United Kingdom government will impose a 20% value-added tax (VAT) on private school fees. This VAT policy echoes the 1944 Butler Act, which had sought to dismantle socio-economic barriers by establishing free secondary education but instead disproportionately benefited middle-class families. Similarly, the current VAT policy risks creating a new stratification, where wealthier families retain access to private education while middle-class families face decreased choices. This essay argues that while the VAT policy seeks to enhance equity, its regressive impacts on middle-class families, strain on public schools, and effect on bursaries may ultimately reduce socio-economic mobility.

A Regressive Burden

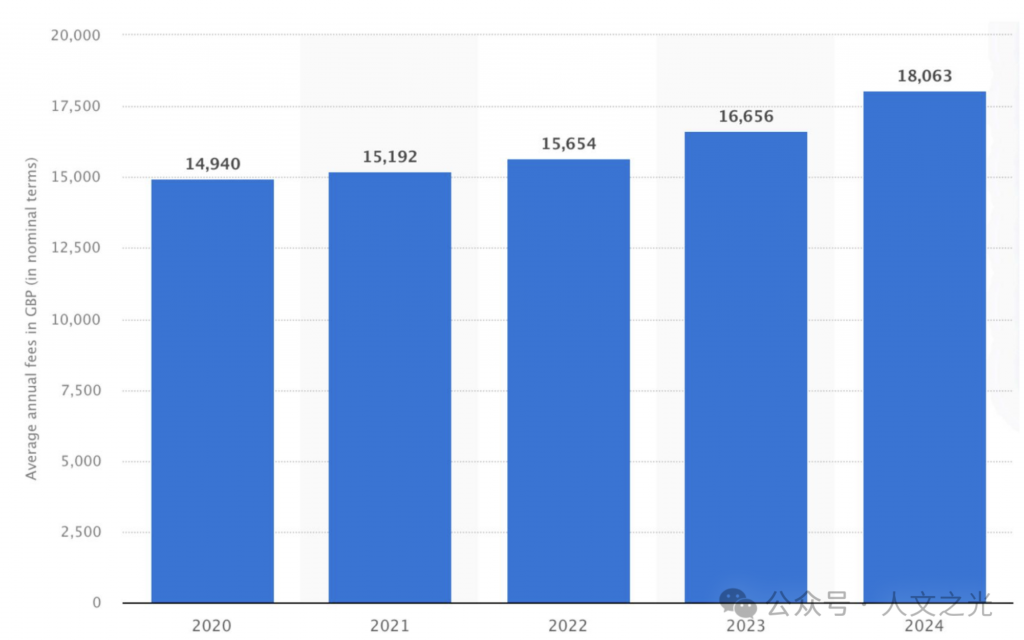

Evidence suggests that the VAT policy has uneven effects across different income groups. Private school fees in the UK averaged £18,063 in 2024 (Fig. 1), representing approximately 45% of the median middle household disposable income. A 20% VAT increase would raise annual costs by £3,600-£8,000 per child, equaling almost 20% of UK middle-class families’ annual income. This increase in financial burden causes a disturbance amongst varying levels of price sensitivity among private school families. Surveys estimate that “42% of privately educated children could see their education disrupted,” totaling up to 134,800 students removed from private schools directly because of VAT.

The current VAT on private schools risks replicating the harmful consequences of the 1997 abolition of the Assisted Places Scheme (APS), which stripped 75,000 high-achieving, low-income students of access to elite education. The APS had provided subsidized private school placements—a proven mobility ladder, with beneficiaries being twice as likely to attend top universities compared to public school students. Former Member of Parliament Cheryl Gillan warned this would turn private schools into a ‘socio-economic exclusive zone,’ contributing to the gap between those who could and couldn’t afford private education.

On the other hand, high-income families are unlikely to be deterred by a 20% VAT. These families demonstrate a significantly lower price sensitivity to the VAT, as tuition fees represent a lower percentage of their incomes. Wealthier families, thus, can maintain enrollment while middle-class families face higher financial barriers.

The reduction in middle-class participation in private schools raises questions about whether social mobility is as accessible as previously. Socio-economic mobility is defined as how one’s social and economic situation changes relative to one’s parents, and it hugely relies on the abilities of families to invest in their children’s futures. Oxford Open Economics identifies that privately educated individuals have considerable advantages over “others who were equally hard-working and talented, but educated in a public school.” These patterns suggest that private education may facilitate career and future economic advantages. However, the introduction of VAT reduces the ability of middle-class families to utilize private education as a mobility pathway: Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century has already warned in 2013 that regressive taxes on education can exacerbate wealth concentration.

Public School Capacity: A Systemic Backfire

As families unable to afford the VAT move their children to public schools, public schools may face pressure due to increased enrollment. Current data suggest that even a modest shift in enrollment could strain the public education infrastructure: according to 2023 figures, 24% of secondary schools and 16% of primary schools already operate at or above their official capacity. In addition, projections by the UK Parliament estimate that 134,800 additional pupils will end up in public schools due to VAT, costing the treasury £1.1 billion. Meanwhile, public schools currently face a shortage of 200,000 teachers. This VAT-led influx risks further diminishing educational quality through larger class sizes—at present, public schools average 8.3 more students per class than private ones. Overcrowded classrooms tend to encourage passive learning and decrease educational effectiveness. This change thus disproportionately harms disadvantaged students already in public schools by diluting resources for those with few alternatives apart from studying.

The resulting pressure on public schools creates a multilayer threat to socio-economic mobility. First, middle-class families forced out of private education by VAT will encounter overcrowded public schools with decreased resources. Second, disadvantaged students already in public schools face further reduced opportunities as resources become diluted to accommodate increased numbers of students. Third, VAT encourages a wider social gap between the middle and upper classes by eliminating opportunities for middle-class families to invest in their children’s education. By weakening both pathways for advancement—private education for the middle class and quality public education for lower-income families—the VAT policy entrenches inequality rather than mitigating it. This systemic strain of resources demonstrates how fiscal measures targeting private education can hinder mobility across income groups when the current situational conditions are not properly considered.

Unintended Economic Burdens: Bursaries

Private schools in the UK serve as a critical maintenance of socio-economic mobility through their bursary programs, which currently provide £938 million annually to 157,000 students from low-income households. These programs have proven to be remarkably effective: recipients of private school bursaries are 43% more likely to receive offers from Oxford and Cambridge universities, and they go on to earn 7% higher average incomes according to longitudinal studies. For disadvantaged students, bursaries represent one of the few reliable pathways to elite educational networks and upward social mobility.

The implementation of VAT now jeopardizes this vital mobility route. The VAT’s erosion of bursaries directly contradicts John Rawls’ Theory of Justice by diminishing disadvantaged students’ rights to access equal educational opportunities compared to those financially supported. Data shows that 63% of private schools are forced to reduce bursary allocations due to the introduction of VAT. This reduction stems directly from schools reallocating funds to cover VAT costs, with mid-tier institutions typically cutting bursary budgets by 35% when faced with £20,000 fee increases. The consequences are severe: when bursaries are withdrawn, dropout rates among low-income private school students increase by 22%, and their likelihood of attending top universities decline by half.

This creates a perverse outcome for social mobility. Low-income students are no longer financially supported to attend private schools, which, going back to the definition of socio-economic mobility, is a farming factor since parents are no longer able to invest in their children’s futures. While the VAT policy aims to reduce educational inequality, its practical effect has been to eliminate one of the most effective mechanisms for talented disadvantaged students to access elite education and a better future. Through constraining one of the UK’s most proven mobility channels, the tax risks leaving disadvantaged students with fewer opportunities for advancement while doing little to address systemic inequities in educational access.

Policy Rationale

While there are certain drawbacks to the VAT policy, its theoretical advantages may have suggested otherwise before the policy was implemented. The UK government justifies its advantages on three core areas: resource redistribution, educational equity, and social integration.

First, policymakers highlighted that this measure corrects an imbalance in education. Prior to the implementation of VAT, private schools benefited £3 billion annually from charitable tax exemptions. Fiscal analysts note that the £10.2 billion income of private schools represents an underutilized revenue stream, especially under current situations when public budgets are strained. By redirecting the £1.5 billion in projected annual VAT revenue to public education, it could help address the £700 million gap in public school funding.

Second, by redirecting students from private to public schools through this fiscal policy, the government creates a more unified education system where access to education is determined less by financial capacity. In principle, this approach seeks to enhance socio-economic mobility by redistributing educational resources more equally across the society. The policy operates on the theoretical framework that standardized access to education, when combined with improved public school funding from VAT revenues, will allow academic merit rather than financial privilege to become the primary determinant of educational outcomes.

It also preserves socio-economic mobility pathways by maintaining middle-income families’ access to better education. The VAT generates substantial revenue that is reinvested directly into public schools, targeting the root causes of limited mobility. These funds result in improved facilities and enhanced teacher training programs in public schools. By narrowing the quality gap between public and private schools, the policy ensures that children from lower-income backgrounds receive the support they need to compete on equal footing. Unlike bursaries—which benefit only a select few—this approach lifts entire communities, creating broader pathways to success. Also, the VAT in theory would serve as a perfect tool to break the enclosed cycle of elite privilege constrained to private schools. Private schools have long served as gatekeepers to elite universities and high-paying careers. Now, more resources will flow toward public schools, fostering an environment where merit, not family income, determines achievement. Over time, this reduces the outsized advantage privately educated students hold in admissions to top universities and high-income professions.

However, these theoretical benefits are based on two crucial assumptions: first, that the quality gap between private and public education can be sufficiently narrowed through additional funding generated by VAT alone, and second, that restricting access to private education will necessarily result in more equitable outcomes rather than simply limiting options for middle-income families while the wealthiest maintain their advantages. Actual outcomes prove that the two main assumptions held are nearly impossible to achieve in reality under current societal circumstances.

Alternative: Progressive VAT

An alternative policy that solves certain defects of the current policy would be to implement a progressive VAT system: applying progressively higher rates to different tuition brackets. Under this model, the first £10,000 of annual tuition fees would remain VAT-free, protecting low-tuition private schools serving modest-income households. Fees between £10,000 and £30,000 would incur a 10% VAT, while only amounts exceeding £30,000—typically charged by elite boarding institutions—would face the full 20% rate.

Three key advantages distinguish this approach from the flat VAT model. First, it preserves socioeconomic mobility pathways by maintaining middle-income families’ access to better education and more opportunities. By classifying attending students based on tuition fee, this is a reliable method to assess a family’s financial ability and not accidentally injure low-income families in private schools. Second, it maintains fiscal benefits by generating tax revenue from wealthy families who choose to persist in private schools. Third, the progressive VAT scale will likely incentivize private schools to rationalize their fee structures, possibly lowering tuition fees and thus opening more opportunities for students at affordable private schools. The Human Capital Theory purpose education as an investment with lifelong returns. The progressive VAT aligns with this by preserving middle-class access to private education, a critical mobility pathway. Conversely, the flat VAT undermines this principle by pricing out families whose investment in education could yield high social returns. Though a progressive VAT generates less revenue, it better balances equity and mobility than the flat 20% rate.

Conclusion

The UK government’s imposition of VAT on private school fees represents a well-intentioned yet slightly flawed approach to addressing educational inequality. While the policy succeeds in generating funds for public education, it disproportionately harms the socio-economic mobility of middle-class and low-income families it aims to help. An enhancement of socio-economic mobility requires policies that address inequality without eliminating proven pathways—a balance that this VAT fails to strike. While no policy is perfect, the VAT represents a necessary step toward dismantling the rigid structural advantages that the wealthy receive. By redirecting resources to where they are needed most and ensuring that wealth no longer buys unparalleled educational privilege, the UK can build a society where success is determined by effort and ability.